Why do our prices stay high despite global dip?

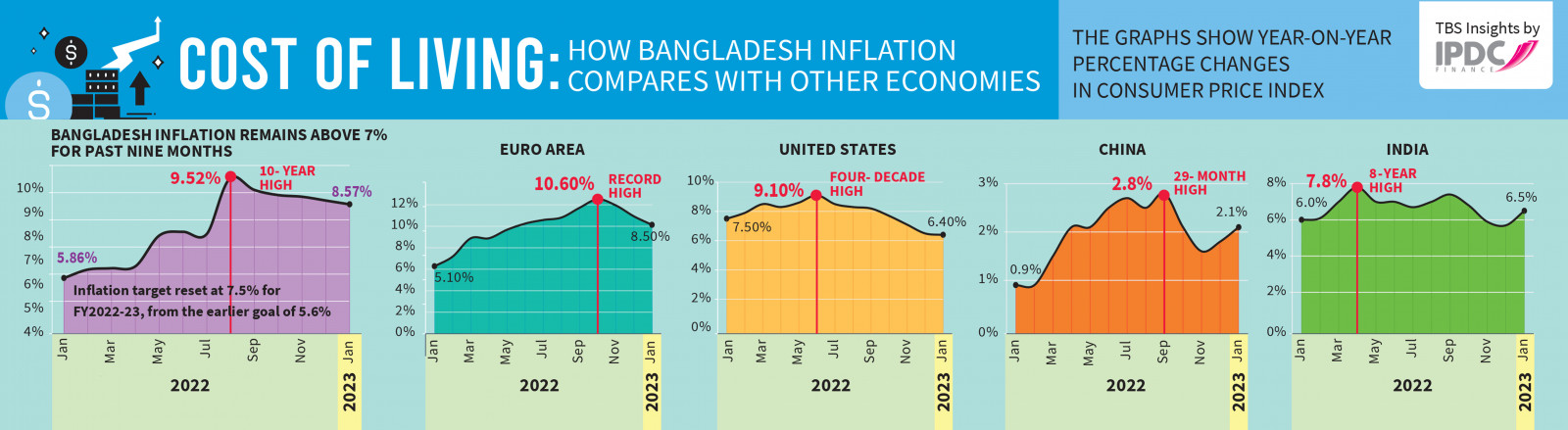

Inflation rates are falling in many parts of the world, including war-affected European countries and the United States, defying expert predictions. Close at hand, China and India are also experiencing a decline in inflation in line with the global trend.

However, the situation is different in Bangladesh where commodity prices go up briskly with any uptick in the international market but show an obstinacy even when global prices fall.

Data show that the US inflation dropped to 6.4% this January from the four-decade high of 9.10% in June last. Similarly, Germany's inflation decreased by one-fourth from a record high of 10.4% in October, and the Euro area experienced a 2.1 percentage point drop in inflation in January this year compared to October last, thanks to declining commodity prices in the global market.

But in Bangladesh, the drop in the inflation rate has been rather weak, with the rate decreasing to 8.57% in January 2023 from a 10-year high of 9.52% in August last year.

This indicates that prices tend to rise faster than they decline, even when commodity prices fall in the international markets.

For instance, the global price of wheat dropped below $8 per bushel on 17 February, but the local market price of the cereal in Bangladesh did not decrease. Currently, one kilogram of flour is selling for Tk68 in Bangladesh, up by over 51% year-on-year. Similarly, the global commodity market prices of soybean oil and the price of crude oil dropped to pre-war levels, but local prices did not follow suit.

Even the government-set fuel oil prices did not decrease despite prices going down in global markets.

According to economists, several reasons may contribute to the slow pace of inflation reduction in Bangladesh. One reason is the depreciation of the local currency by 25% since the Russia-Ukraine war began on 24 February last year. Another reason could be an energy price hike and a lack of adequate policy measures, both fiscal and monetary.

In some cases, local market prices may be influenced by factors such as market dominance by a few companies, which can make it difficult for consumers to benefit from global price decreases, said the economists.

Dr Monzur Hossain, research director of Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS), suggested that inflation in Bangladesh is not declining at the same pace as in other countries because of the significant exchange rate depreciation and recent energy price increase.

He explained that raising interest rates to tame inflation is a common practice, but Bangladesh could not do that. Additionally, some counter-inflationary measures, such as selling essentials at subsidised prices for marginalised people and wage and salary hikes, could not be implemented in Bangladesh.

Dr Monzur forecast that even though commodity prices have started dropping in the global market, inflation will not decrease in Bangladesh anytime soon as it is related to the crisis in dollar supply in the country for which import of adequate amounts of goods has been hindered.

The economist suggested that policymakers need to analyse the pass-through impacts of price hikes of commodities in the international market to manage inflation effectively.

Mostafa Kamal, chairman of Meghna Group of Industries, attributed Bangladesh's sticky inflation to the depreciation of the local currency and the crisis of the US dollar.

"Consumers should be benefiting from decreased prices, but the exchange rate disadvantage is preventing that," he said, adding that he is still opening letters of credit (LCs) at higher rates than the bank rate.

Moreover, Kamal pointed out that there is a shortage of goods in the market that is discouraging competition and fair prices.

Customs data show that Bangladesh imported 26.85 lakh tonnes of wheat in the first seven months (July-January) of FY23, down from around 35 lakh tonnes during the same period a year ago.

But industry insiders said large commodity importers incurred huge losses last year because of the exchange rate. They opened LCs at Tk86 a dollar but settled those payments at over Tk100/dollar.

Now they are making up those losses by passing those on to consumers, said a top official of a leading commodity trading company.

What strategies do other countries adopt to tame inflation?

Even though strategies depend on a country's specific economic situation and policy objectives, there are some common methods that are used widely across the world.

First comes monetary policy. Central banks adjust the money supply by changing interest rates to control inflation. By raising interest rates, they can reduce the demand for goods and services and slow down the economy, leading to lower inflation.

For instance, the Federal Reserve Bank of the USA raised its benchmark interest rate several times to take it to 4.75% from nearly zero a year ago.

Defying calls for rational action, the Bangladesh Bank kept the lending rate cap at 9% which was set in 2020 when the demand for money was at the lowest level because of the lockdown and a significant slowdown in economic activities.

The inflation rate rose to a 10-year high of 9.52% from less than 6% a year ago, but the central bank kept the lending rate unchanged despite repeated calls from the banks and economists.

Secondly, fiscal policy. Governments can use their taxation and spending policies to influence inflation. For example, Bangladesh could have reduced taxes on imported items, at least for essential food commodities, to bring the prices of those goods down.

Also, countries can use an exchange rate policy to control inflation by adjusting their currency's value. A weaker currency can increase the price of imported goods, leading to higher inflation, while a stronger currency can decrease prices. Weakening the Taka has been stoking inflation in Bangladesh.

Then there are supply-side policies. Countries can take steps to increase the supply of goods and services in the economy, which can help to reduce inflation. This can include measures such as reducing regulations, investing in infrastructure, and promoting competition.

Besides, some countries use indexation to automatically adjust wages and prices in line with inflation which can help to stabilise the economy and reduce the impact of inflation shocks. However, this method can also lead to a wage-price spiral, where rising prices lead to higher wages, which in turn leads to higher prices.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel