Have testing charges affected the number of Covid-19 tests in Bangladesh?

With a population of around 180 million, and with limited resources and infrastructure, employing rapid test kits for Covid-19 screening could have alleviated the financial burden for the majority of the people

In recent weeks, Bangladesh has observed a steep rise in the cases of coronavirus (Covid-19) which is currently at 274,525 confirmed cases and claimed 3,625 lives, till August 15, 2020.

While some countries (e.g. South Korea) have recorded success through the implementation of the "test, trace and contain" policy to flatten the Covid-19 curve, Bangladesh, unfortunately, ranks the second lowest country in the world in terms of number-of-tests to population-size and also failed to attain a 20,000 daily test frequency.

With only 5,137 tests per millions of people, Bangladesh practically ranks only above Mexico, and this rate is even well below its South Asian counterparts.

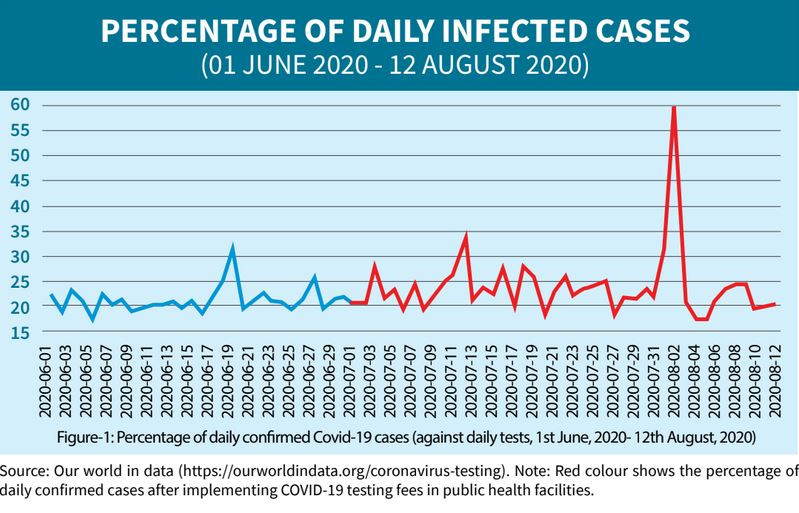

With an average confirmed rate of 15-20% of the total conducted tests in recent weeks (see Figure 1), implementing imposition of charges for Covid-19 testing in public hospitals in late June is certainly an ill-planned policy by the government, which will further exacerbate the pandemic in coming days.

Figure 1: Percentage of daily confirmed Covid-19 cases (against daily tests, 1st June, 2020- 12th August, 2020)

Source: Our world in data (https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing). Note: Red colour shows the percentage of daily confirmed cases after implementing COVID-19 testing fees in public health facilities.

Till date, Covid-19 testing in public hospitals in South Asian countries remains free except in Bangladesh where the cost could vary between US$2.36 and US$5.89, depending on the sample collection method.

The authorities maintained that such pricing mechanism was implemented to avoid unnecessary testing and restore efficiency to the pandemic management, but these justifications have been deemed unsatisfactory by the experts.

Patients were already being screened by professionals before the collection of their samples, and the current mismanagement will certainly discourage a healthy person from undergoing testing if they do not have symptoms of Covid-19. Thus, the statement on unnecessary testing being done by the people is untrue.

A variety of reasons exist as to why the implementation of Covid-19 testing charges may be unsuccessful, and even worsen the pandemic situation in Bangladesh.

First, introducing a price tag will certainly demotivate potential patients from testing for the Coronavirus as many would be unable to afford the cost of testing.

This is unwarranted as the Covid-19 pandemic has been projected to plunge a minimum of 33 million people into poverty, in a country where already, one in five people live below the poverty line with an average wage of less than $5 a day before the advent of the pandemic.

Certainly, these economically vulnerable group of people would be unable to afford the cost of testing.

Second, in many developed and developing countries, insurance providers cover the cost of Covid-19 testing; but in contrast, the insurance penetration rate remains the lowest in Bangladesh (only 0.55% of GDP) amongst other emerging Asian countries.

Consequently, the majority of Bangladeshis need to solely bear the cost of testing, which will certainly deter them from getting tested. The recent evidence also supports our argument, as the number of tested samples in the country declined from 18,426 (on 30th June 2020) to 10,759 (on 9th August 2020), after the implementation of testing fees (see the Figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of daily Covid-19 tests (before and after implementing fees)

Sources: Our world in data (https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus-testing). Note: Red colour shows the number of tests after implementing COVID-119 testing fees in public health facilities.

Third, in a bid to motivate frontline workers, the government also announced monetary rewards for public servants that get infected or die from the Covid-19; which has been deemed as a praiseworthy move. However, charging the general public to get tested is somewhat discriminatory and may result in rapid transmission of the disease in the country.

Fourth, as per the experts' opinions, more tests are indeed needed to control the transmission of Covid-19 across the country. Implementing fees to get tested for Covid-19 in public health facilities is going against this policy suggestion of many, as we have seen a decline in the number of tests per day and increase in the percentage of affected people in Bangladesh (Figure 1 & 2).

As a result, we propose that instead of introducing testing charges, the government could have resorted to other initiatives such as better screening before sample collection. Moreover, since the Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) test is relatively expensive and time-consuming, a more affordable testing method such as the use of rapid test kits (e.g. Antigen based test) could have been employed just like other countries (e.g. India) to ramp up testing capacity and better utilise public resources.

With a population of around 180 million, and with limited resources and infrastructure, employing rapid test kits in Covid-19 screening could have alleviated the financial burden for the majority of the people.

Provision of basic health facilities is one of the core agenda of any government, particularly in this period of the pandemic. In the event of millions of job-losses due to Covid-19, imposing fees for testing in public hospitals in Bangladesh is synonymous to 'adding fuel to fire'; and we fear that due to this price tag, many will not get tested and may die without even knowing they were infected with the virus.

Hence, it becomes imperative for the government to review its decision on implementing Covid-19 testing charges before the virus becomes widespread.

Dr Md Aslam Mia works at the School of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM), 11800, Pulau Penang, Malaysia. Email: aslammia@usm.my/

Dr Hasanul Banna works at Ungku Aziz Centre for Development Studies, Faculty of Economics and Administration, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: banna@um.edu.my

Dr Abu Hanifa Md Noman works at Department of Finance and Banking, Faculty of Business and Accountancy, University of Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: abuhanifa@um.edu.my

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel