Who really owns your football club?

Manchester City is on the cusp of proving that it is now the dominant force in European football. Whether the English team wins or loses in the Champions League final this weekend, it's probably a matter of when — not if — that happens. But it might not have turned out that way.

Back in 2007, investors from Dubai attempted to buy Liverpool, only to lose out to US rivals. A Middle Eastern approach for Manchester United was also dismissed by the club's US-based owners, the Glazer family. A year later, the Abu Dhabi United Group for Development and Investment bought Manchester City from a former prime minister of Thailand and promised to bring "the best football players in the world" to the club.

Fast forward, add at least $2 billion spent on players and the latest training facilities, and Manchester City could become the first state-backed club to triumph in the world's best-known club competition. The victory would follow the surprise golf deal struck this week by Saudi Arabia to team up with the PGA Tour, and would underscore the new era where investors with seemingly endless riches are bidding to reinvent global sports.

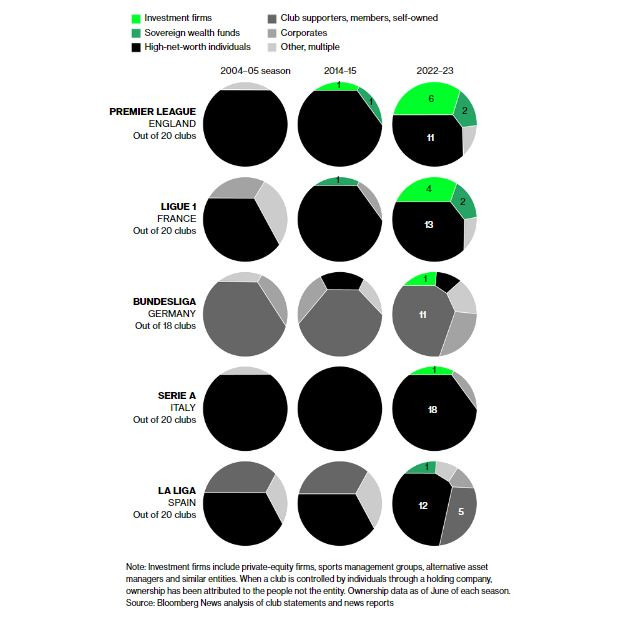

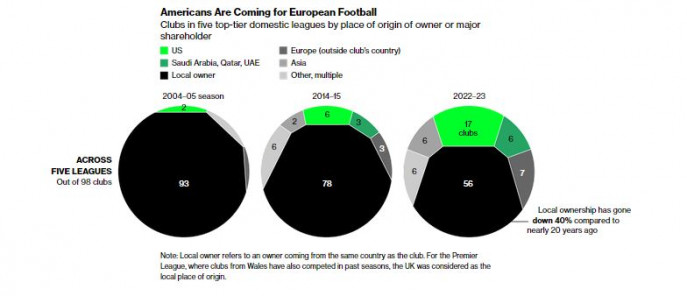

Bloomberg News looked at Europe's top five domestic leagues to uncover how the ownership across 98 clubs has changed since 2005, when the Glazers completed their takeover of City's rival Manchester United for close to $1 billion including debt. The analysis shows how the world's most popular sport morphed from an expensive bit of fun for local bigwigs into a serious play for power and profit.

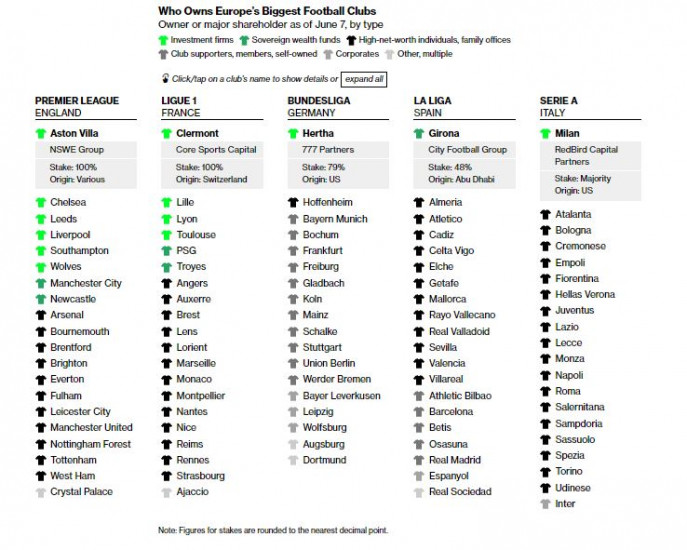

Sovereign wealth funds or their subsidiaries now own five clubs, including Manchester City, whose owners have transformed into City Football Group. Then there's Wall Street. Investment firms, such as private equity, sports management groups and alternative asset managers, own or are the major shareholders in 12 clubs, including England's Chelsea and France's Lyon.

The English Premier League and France's Ligue 1 have seen the most activity among the big leagues Bloomberg News analyzed. Germany's Bundesliga, where the power is held by a club's members rather than owners, Spain's La Liga and Italy's Serie A have seen the fewest transactions.

From AC Milan to Newcastle United, some of the continent's best-known clubs have changed hands. Some new owners are deploying sporting assets as a diplomatic tool. Others are aiming to turn football into the cash cow it's never managed to be. And some are taking advantage of clubs needing money after seeing their finances crippled during the pandemic.

It's easy to see why. The Premier League, Europe's richest domestic competition, only generates marginally more money than the NHL ice hockey league. An attempt to create a lucrative European Super League without the jeopardy of relegation and collapse of income — much like the NFL — failed in 2021, but it hasn't gone away.

The spending spree doesn't look like it's ending. Manchester United is still considering whether to sell to either local billionaire Jim Ratcliffe, a Qatari group enriched by the Gulf state's massive natural gas exports, or to a variety of US hedge funds and asset managers.

But clubs owned by investment funds have found success in the Champions League elusive. Since 2013, when Paris Saint-Germain first made the quarter finals under Qatari control, Real Madrid boasts the most victories, with five wins. The team is run by Spanish billionaire Florentino Perez, who is elected by the members who still own the club rather than any rich individual or group of investors.

Saturday's prestige final gives Manchester City another chance to become the first club owned by a sovereign fund to win Europe's top prize, two seasons after it lost to Chelsea, then owned by Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich. The match in Istanbul sees City play Inter Milan, a team owned by a Chinese retail conglomerate that has borrowed heavily from a US asset management firm.

"In 1983, when I joined the board of Arsenal, it was the local businessman who invested in the club he loved," said David Dein, the former vice chairman of Arsenal in London. "Then it became millionaires, then billionaires and now sovereign states."

So what's changed? Football is no longer a weekend hobby for the rich. Instead, the cost of running a club has pushed out local investors and replaced them with some of the world's richest pools of capital, who are buying clubs not only to make money, but also influence their global standing.

Both Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia now own major clubs in northern England, and look set to become one of the most important property investors in first Manchester, then Newcastle. Gulf neighbor Qatar has also turned Paris Saint-Germain into a luxury asset, replete with a 4,400 square-foot (409 square-meter) store on Fifth Avenue.

Football is a procession of rich men watching even richer men come and throw more money on the table.

Dein made his money as a sugar trader, and bought a 16.6% stake in Arsenal in 1983 for £292,000 ($364,000). The man who he bought from, club Chairman Peter Hill-Wood, called Dein "crazy." "To all intents and purposes it's dead money," he said at the time.

While the size of Dein's stake rose and fell in the following years, by 2007 he sold his remaining 14.58% to Russian oligarch Alisher Usmanov for a reported £75 million.

Usmanov joined fellow Russian billionaire Abramovich, who bought Chelsea in 2003 for £140 million, in the Premier League. Abramovich spent more than $1 billion on players and won 21 trophies as owner of Chelsea. (He was forced to sell the club following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022. A group of US-based investors bought it for about £2.5 billion.)

Newcastle United owner John Hall, a miner's son who made his money mainly from real estate development, sold the club to retail tycoon Mike Ashley a few years after Abramovich bought Chelsea. "No way could I compete with Abramovich," Hall recalled. "I couldn't risk my family business for football. Now billionaires and state funds have taken it to a different level."

Dein summed it up: "Abramovich parked his tanks on our lawn and it was firing £50 notes. New owners today are firing €500 notes."

Today, Dein's former club Arsenal is owned by the holding company of Stan Kroenke. The American is among a group of billionaires in football that also include Dan Friedkin at AS Roma and British businessman Joe Lewis at Tottenham Hotspur. Manchester United bidder Ratcliffe, who made his fortune from oil and chemicals, owns OGC Nice in France.

Clubs were previously owned by an equally eclectic — but less wealthy — group, with proprietors ranging from porn barons to steel magnates. Ownership was more the realization of a childhood dream that — almost always — was destined to lose money, even until recently.

Take Real Zaragoza. By 2014, after an historically successful run despite its modest resources, the Spanish club was close to liquidation. A series of desperate phone calls led to Cesar Alierta, then chief executive officer of Spanish phone giant Telefonica, along with two other local investors, saving the club.

"Alierta's father was the club president in the 1950s so he grew up with that experience at home," said Fernando Sainz de Varanda, the former CEO of Real Zaragoza and Alierta's nephew. "He said his dad would have never forgiven him to not save Real Zaragoza if he had the chance to do so."

Alierta spent more than €8 million ($8.6 million) to save the club, but failed to earn promotion. The dream of taking the club to its old glory was unfeasible. Eight years later, Real Zaragoza was sold to a group of investors including the co-owners of Inter Miami CF and a partner of Ares Management Corp, a US investment firm.

"At the beginning it was mostly local people but there has been the entrance of investment funds that seek profitability," said Sainz de Varanda. "When they bring executives from outside, they will make decisions with the head, not with the heart, and in football there is a very important part that's decided with the heart."

Today, football clubs are just as likely to be owned by foreign investors as by local businessmen. Investment firms and high-net-worth individuals from the US have been the biggest buyers of football clubs in recent years, now owning close to a fifth of the top European teams, compared to just two out of 98 back in 2005. Petro-states have built their investments from million-dollar bets to sporting conglomerates worth billions.

"This industry had been family-owned businesses for many years — now they are major organizations and have to be run professionally," said Jim Miller, partner and co-head of US direct lending and sports, media and entertainment at Ares. "That is an evolution that we started to see over the last 10 years, and there's still runway for improvement."

In 2005, there were no foreign investors in the Italian, German and Spanish leagues, according to the Bloomberg News analysis. Part of the reasoning for the influx of cash since then is that football, despite its global ubiquitousness, has yet to become a money-making machine. And therein lies the potential, goes the thinking.

Compared with US leagues in terms of global dollars generated, the English Premier League is a relative minnow. The NFL brings in about $19 billion a year at present, and the US baseball and basketball leagues make more money than the Premier League, whose teams are expected to bring in about $7 billion. That's only slightly higher than the NHL.

The fact that football's richest league brings in slightly more money than ice hockey is seen as a golden opportunity for foreign investors. In the US, sports teams are often viewed as media assets, defined by local market share and billion-dollar local broadcasting rights.

"A lot of sport leagues and competitions are able to maintain lucrative broadcast contracts, with which comes strong financial benefits for the teams involved, making them more and more appealing as a source of revenue for the new owners coming in," said Minal Modha, research director at Ampere Analysis, a data and analytics firm in London.

European football clubs are also a lot cheaper. A consortium including Egyptian billionaire Mohamed Mansour recently paid $500 million to buy the rights for a new US Major League Soccer team in San Diego. To buy an NFL team, you need billions in ready cash. American investor Robert Platek took over Italian Serie A side Spezia in 2021 for a reported €25 million.

It's not the first time America has piled into soccer — and lost its shirt. The question is now whether the latest crop of owners has the financial acumen to make money.

Private equity investor Ellis Short was one of the first wave of US financiers into English football, buying Sunderland in late 2008. He spent an estimated £200 million on the club, only to see it eventually relegated twice in consecutive seasons. He eventually sold up for a reported £50 million in 2018.

Billionaire Randy Lerner — then owner of the Cleveland Browns — also had a go with Aston Villa, buying the Birmingham club for the equivalent of about $110 million in 2006, selling it for $90 million a decade later, and spending about $400 million along the way.

This time around, football's new investors aren't just rich individuals ready to spray cash around in the bid for glory. Now they're some of the world's most sophisticated investors, normally content to construct complex debt instruments or circle struggling corporate giants.

Manchester City's Champions League final rival Inter Milan is owned by Chinese retail conglomerate Suning. After struggling to finance the team, Inter took out an emergency €275 million loan in 2021 from Howard Marks's Oaktree Capital. If Inter isn't able to repay the debt, the loan could turn into equity and hand Oaktree control of the club, not unlike how Elliott Investment Management gained control of AC Milan, Inter's local city rival, in 2018.

Despite the sophistication of the new investors, some old habits die hard. US private equity firm Clearlake Capital, along with credit investor Todd Boehly, has spent hundreds of millions on players for Chelsea over the past 12 months, only to see the club finish in its worst league position in 30 years and miss out on a place in lucrative European tournaments.

Others spent, too, but have succeeded. Newcastle United was bought in October 2021 by a consortium led by Saudi Arabia's sovereign wealth fund for £300 million. That's about $70 million less than the as-yet-to-be created San Diego franchise.

Newcastle has been one of England's biggest football clubs, but has languished — last winning a trophy in 1969. In its first year under the Saudis, the club spent over £100 million to avoid relegation. It kept on spending and has now qualified for the Champions League for the first time in two decades.

Not everyone wants outside interference. Germany's Bundesliga boasts well-run and successful clubs like Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund. But for investors, it's an unwelcoming place because of strict ownership requirements that have for decades favored fans over financiers.

Rules prevent a commercial investor from holding more than 49% of voting shares in any club, giving fans co-ownership and a say in strategic decisions. The edict has been credited with keeping wage bills and ticket prices low, but it's also prevented the Bundesliga from signing the kind of multi-billion-dollar deals that have bolstered its European rivals.

"Buying into a football club, but not getting the power to freely make decisions — that's a very unattractive model for large investors," said Sascha Raithel, a marketing professor at Berlin's Free University.

There are exceptions. VfL Wolfsburg is owned by carmaker Volkswagen AG and Bayer 04 Leverkusen by pharmaceuticals giant Bayer AG. They're exempt from the rules because their owners have invested consistently over more than two decades. RB Leipzig is backed by Austrian energy drink maker Red Bull GmbH.

And even in this last bastion of "how it used to be", Americans are also making inroads. Miami investment firm 777 Partners LLC this year bought a stake in Berlin's Hertha BSC, after David Blitzer, the Blackstone Inc. executive, broke ground two years ago by investing in Augsburg.

"Football in general and football clubs in particular have a unique power and place in people's lives," said Josh Wander, co-founder of 777 Partners, which also owns Italian club Genoa, Vasco da Gama in Brazil and Standard Liege in Belgium. "We believe that the extent to which this relationship has been harnessed has only just started to be realized."

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel