Invisible plastic, visible threat: The hidden danger of microplastics and how to protect yourself

These tiny plastic particles, often smaller than a grain of rice, have infiltrated the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe, raising urgent questions about health, environmental sustainability, and economic cost

Highlights:

- Microplastics infiltrate Bangladesh's air, water, food, people

- Rivers transport one million tons of mismanaged waste annually

- Plastic use tripled; pandemic worsened crisis with massive waste

- Pollution costs Bangladesh $39 million yearly in damages

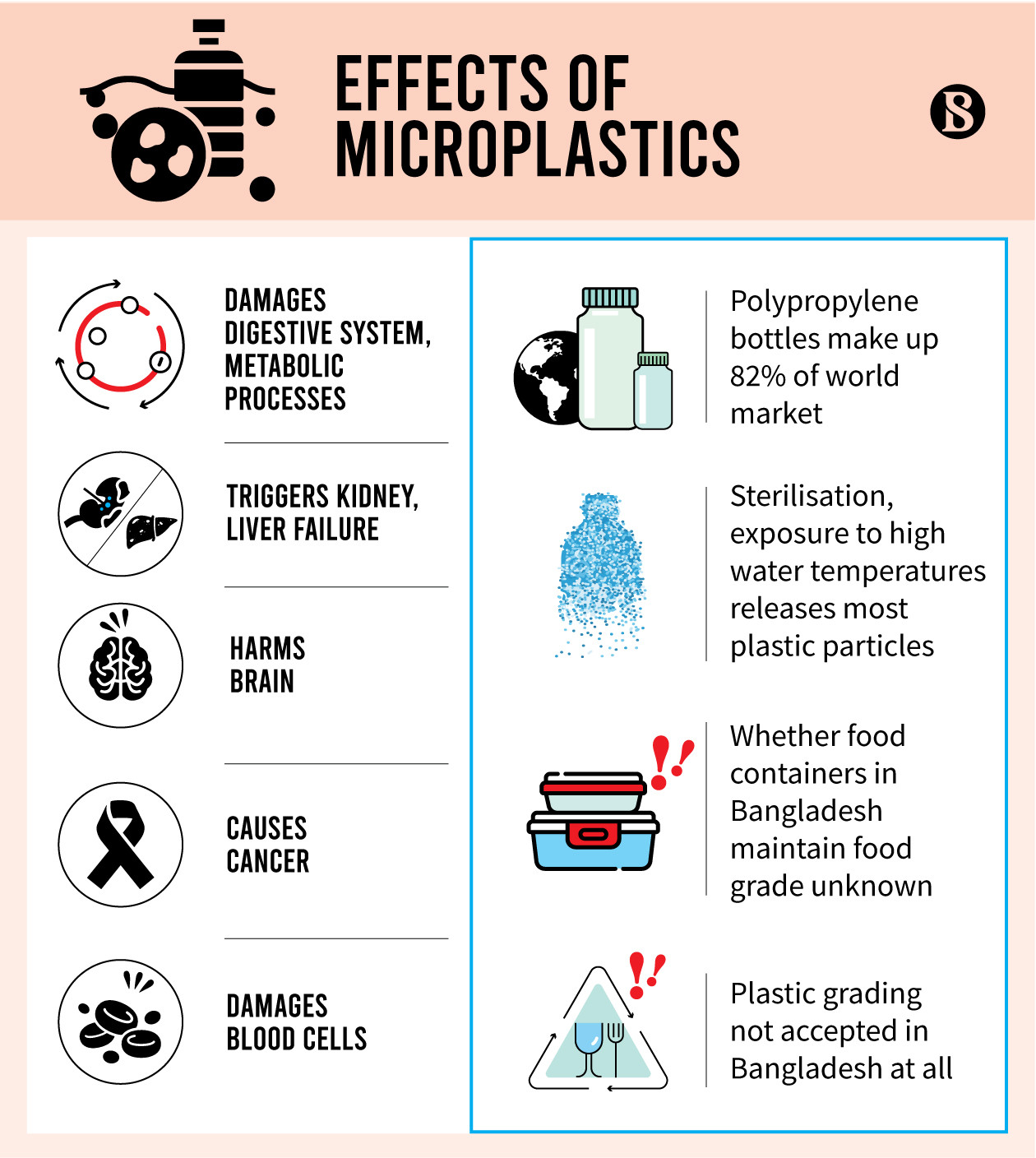

- Microplastics may cause inflammation, organ damage, and toxic exposure

- Systemic policy, recycling, and innovation needed to curb crisis

From the water flowing in its rivers to the air filling its cities, Bangladesh is increasingly confronting an invisible invader: microplastics.

These tiny plastic particles, often smaller than a grain of rice, have infiltrated the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe, raising urgent questions about health, environmental sustainability, and economic cost.

Microplastics: Tiny and everywhere

Microplastics are fragments of plastic less than 5 millimeters in size, with even smaller nanoplastics capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier.

They originate from primary sources, such as microbeads in cosmetics, and secondary sources, which result from the breakdown of larger plastic items, like bottles and packaging.

Estimates suggest humans may ingest the equivalent of a credit card's worth of plastic each week, highlighting the ubiquity of this contamination.

Globally, studies have found microplastics in bottled water, seafood, vegetables, honey, bread, and even salt. Bottled water, for instance, can carry six times more microplastics than tap water, with some samples containing up to 240,000 nanoplastic particles per litre.

Beyond ingestion, these particles are airborne and can be inhaled, and they can also be absorbed through skin contact from synthetic clothing or cosmetic products.

As a result, microplastics have been detected throughout the human body, including in blood, arteries, and vital organs such as the heart, liver, and brain.

Bangladesh's plastic problem

For Bangladesh, the issue is compounded by its economic growth, population density, and reliance on plastic-intensive industries.

A review of data from 2014 to 2024 shows microplastic contamination is widespread in rivers, soils, air, fertilizers, and food products.

Major rivers including the Meghna, Karnaphuli, and Rupsha serve as significant pathways for plastic pollution, transporting an estimated one million metric tons of mismanaged waste annually to coastal areas.

Plastic polymers such as polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene, polyethylene terephthalate, and polyamide dominate the contamination profile.

Primary sources include fishing nets, industrial discharge, and urban waste, while ineffective waste management and a surge in single-use plastics exacerbate the problem.

Bangladesh's plastic consumption has tripled over the past two decades, rising from 3 kg per capita in 2005 to 9 kg in 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic intensified the crisis, generating 21 billion polythene bags and an additional 78,433 tons of waste.

The economic and social costs are substantial. Plastic pollution drains approximately $39 million annually from the Bangladeshi economy, impacting fisheries, tourism, municipal services, and public health.

Cleanup efforts alone consume nearly 30% of the country's environmental budget, while contamination of seafood—an important export commodity—poses threats to international markets.

The risks

Health researchers warn that microplastics may act as carriers for harmful chemicals, including endocrine disruptors, heavy metals, and persistent organic pollutants.

These particles can accumulate in human organs and tissues, potentially contributing to inflammation, oxidative stress, and disruptions in metabolism.

While definitive long-term studies on humans are limited, the global scientific consensus frames microplastics as a significant public health concern.

Practical steps to reduce exposure

Experts stress that while individual measures cannot fully eliminate exposure, they can significantly reduce the risk.

In the kitchen:

Avoid heating food in plastic containers. Microwaving plastic can release millions of microplastics and billions of nanoplastics. Glass or ceramic containers are safer alternatives.

Rethink food storage: replace long-term plastic storage with glass or metal containers.

Choose kitchen utensils made of wood, stainless steel, ceramic, or glass instead of plastic, especially for cutting boards, spatulas, and whisks.

Prioritize fresh, whole foods over ultra-processed options and rinse grains, meat, and vegetables before cooking.

Drinking water:

Prefer tap water over bottled water; the latter often contains far higher microplastic concentrations.

Use home water filters, particularly carbon filters certified to remove microplastics, or boil water to reduce contamination.

Drink from glass or stainless steel bottles and cups rather than plastic.

Policy and collective action is needed

Despite these personal measures, researchers emphasize that systemic solutions are crucial. The root cause lies in fossil fuel-driven plastic production.

Bold policy interventions, such as stronger waste management, stricter regulations on plastic producers, and innovative recycling and circular economy initiatives, are necessary to protect public health and ecosystems.

Simulations suggest that multi-pronged approaches—achieving 69% waste conversion, 80% source separation, and reducing riverine plastic discharge by 50%—could be effective in mitigating the crisis.

Experts call for international collaboration, technological innovation, and enforcement of environmental policies as essential components of a sustainable strategy.

Looking ahead

With plastic production and consumption continuing to rise, Bangladesh faces a crucial decision point.

Without decisive action, per capita plastic waste could rise to 11.6 kg by 2040, landfills could swell to 70,000 tons, and rivers could discharge even more plastic into the environment. Addressing microplastic pollution is not only an environmental imperative but also a public health and economic priority.

As Tracey Woodruff, a leading researcher, puts it: "The burden shouldn't be on me as the consumer to figure out if products can be toxic."

In Bangladesh, where microplastics are already a visible threat in an invisible form, the challenge is clear: coordinated action, policy enforcement, and community awareness are urgently needed to stem the tide of plastic pollution before it overwhelms the country's waterways, ecosystems, and health.

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel