Proposed EU GSP Scheme for 2024-34: What Bangladesh must do now

As Bangladesh is set to leave the group of the least developed countries (LDCs) in 2026, the most important change that it is going to face will be associated with preferential market access for exporters.

Apparel export from the country has immensely benefited from LDC-specific trade preferences granted by various countries through their respective Generalised System of Preferences (GSP). Of these, none was more instrumental in making Bangladesh an LDC export success story than the EU GSP scheme.

Taking advantage of its Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative – designed for providing unrestricted market access of LDC goods under relaxed rules of origin (RoO) requirements – Bangladesh's exports to the EU (including the UK) expanded rapidly from $2.5 billion in 2000-01 to a peak of about $23 billion in 2018-19 before being hit by Covid-19.

The EU and the UK together account for about 60% of Bangladesh's merchandise exports, more than 90% of which comprise textile and clothing items. And almost all of it has benefited from EU duty-free access.

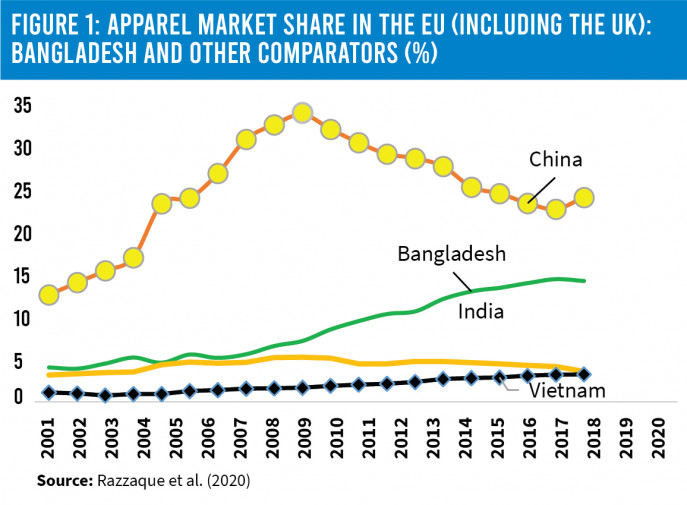

As a result, Bangladesh managed to steadily expand its apparel market share in the EU. During 2010-20, as China's EU apparel market share fell from 30% to 22%, Bangladesh saw its share doubling from 6.5% to 13% (Figure 1).

The significance of the EU GSP scheme becomes clear when comparison is made with the apparel market in the United States, which never allowed duty-free access for Bangladesh's clothing items.

In 2000, Bangladesh had almost an identical apparel market share (of 3.3%) in the EU and US. A lack of preferential market access has resulted in only a modest growth in Bangladesh's export market share in the US vis-à-vis a much stronger performance in the EU (Figure 2).

The EU GSP also offers quite attractive preferential treatment to other non-LDC low-income and lower middle-income countries depending on their ability to meet certain pre-specified requirements. That is why such preference remains extremely relevant even after LDC graduation.

The current EU GSP regime will expire in 2023 and will be replaced by a new one from the beginning of 2024. It has been known that under the existing rules, Bangladesh, after its LDC graduation, would not qualify for the most attractive preferential scheme for non-LDC countries, known as GSP+.

Generally, accessing GSP+ opens the possibility of getting duty-free access to 66% of EU tariff lines including textile and clothing items, and is of interest to Bangladesh after its LDC graduation.

Given the due expiry of the current system, the implications for Bangladesh would only be clear from the provisions of the new GSP replacing the existing regime.

Proposed EU GSP for 2024-34 and implications for Bangladesh

In September 2021, the EU unveiled its proposed GSP for 2024-2034. Understanding various provisions of the proposed system is critical for assessing preferential market access opportunities for different export products in the post LDC period.

The key implication that can be deciphered from the newly proposed GSP provisions is that Bangladesh is likely to qualify for GSP+ after its LDC graduation but the specified EU 'safeguards' would exclude the country's clothing exports from any tariff preferences.

Given Bangladesh's LDC status until 2026 and the fact that the EU allows for an additional three-year transitional period after graduation, Bangladeshi exporters should expect to enjoy the current duty-free market access until 2029.

The proposed system suggests certain changes to the eligibility criteria. It removes the so-called 'import-share criterion', which, under the current rules, is an obstacle for Bangladesh in qualifying for GSP+.

The new proposal expands the list of international conventions to be ratified and implemented by a recipient country to 32 (from the current list of 27). Bangladesh has already ratified all but one of those conventions, paving the way for fulfilling this criterion, albeit implementation being somewhat challenging in some cases.

Despite those apparently positive alterations, the proposed scheme, quite strikingly, has failed to provide respite to GSP+ beneficiary countries from the EU's safeguard measures against textile and clothing items.

According to the stipulated provisions, if the combined share of HS Sections 61, 62, and 63 (comprising knitwear, woven and home textile items and defined as "product group S-11b") from a country exceeds 6% of the total EU imports of the same products, safeguard measures would be triggered to remove duty-free market access for these products.

It is estimated that the combined share of Bangladesh's exports of HS Sections 61, 62, and 63 (S-11b) in total EU imports is close to 9% and is thus already above the threshold value of 6% (Figure 3).

Even with this high share it would be possible to obtain GSP preferences if Bangladesh's share of S-11b products as percentage of all EU GSP-covered imports of the same products were less than 37%. The corresponding Bangladesh share is estimated to be almost 50%.

All this implies that Bangladesh will benefit from GSP+ preferential access, however, its apparel items will face MFN tariff rates in the EU. That is, if the proposed rules remain unchanged, the average tariff rate on apparel exports from Bangladesh to the EU will rise from the currently zero to on average close to 12%.

It is true that accessing GSP+ means continued duty-free access in many other items, and it will help obtain less-than-MFN tariff rates in several categories of goods. Leather goods and footwear are examples of such products. However, the current supply-side capacity in these sectors is quite limited. As such, after LDC graduation EU GSP will be a relatively ineffective instrument for supporting exports.

Graduation would also imply more stringent rules of origin to benefit from any preferential treatment. The minimum local value-addition, for all exports other than clothing, would rise from 30% to 50%. This can further constrain the already weak export supply response.

If apparel exporters would not be receiving any duty benefits, complying with rules of origin will not be needed. Otherwise, after graduation (either under GSP+ or Standard GSP), clothing items must go through what is known as 'double transformation', (i.e., domestically produced fabrics to be used in making garments).

What Bangladesh must do now

The newly proposed GSP regulations will have to be adopted by the European Parliament and this is currently anticipated for the last quarter of 2022. There is thus a limited but potentially invaluable window of opportunity to engage with the EU so that the required changes can be incorporated to keep GSP+ countries (like EBA beneficiaries) out of safeguard provisions, enabling Bangladeshi apparel exporters to continue with duty-free access.

Convincing arguments must be presented in requesting the EC to consider adjustments that will make the new arrangements fair and developmentally impactful.

First and foremost, it must be pointed out that the impact of safeguard measures will be contradictory to the intent of the proposed new regime. In the preamble (paragraph 24) to the new proposal, it is stated that product graduation should not apply to GSP+ and EBA beneficiary countries. But the likely exclusion under safeguards will be tantamount to product graduation.

There is merit in pointing out that Bangladesh's excessive concentration of exports in clothing is widely regarded as a sign of vulnerability. Letting the duty-free access for this sector to discontinue under GSP+ will only aggravate this vulnerability.

The proposed GSP rules will create a unique circumstance in which Bangladesh qualifies for GSP+ but more than 90% of its exports to the EU face the average tariff rate to rise overnight from the currently zero percent to 12%.

This signal of a forthcoming drastic shift in the EU tariff regime will seriously undermine the medium-to-long term perceived competitiveness of Bangladesh's clothing sector, affecting investment prospects. This will certainly not help Bangladesh's sustainable development, which the EU aspires to achieve through the changes in its GSP regime.

In its submission to the EU, Bangladesh should strongly argue that the provisions in the new GSP rules can be regarded as unfair. There are countries that were never LDCs but still benefit from GSP+ (including their textile and clothing exports). These include Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and the Philippines. Even such relatively advanced developing countries, known for their export competitiveness and capacities, as India and Indonesia can access Standard GSP benefits for their apparel exports. Against this, the possibility of a graduating LDC like Bangladesh's forgoing tariff preferences altogether would clearly be contrary to the argument of a GSP regime being development friendly.

The author is Research Director, Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, and Chairman, Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID)

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel

Keep updated, follow The Business Standard's Google news channel